Francis Davis Millet was appointed by President Taft to be the Chairman of the Niagara Falls Preservation Commission. In this capacity Millet oversaw the major survey of the falls and the surrounding area, then under risk of being over used and despoiled for all time. A primary report was issued, under Millet’s leadership on Dec 7, 1911. A supplemental report on the operations of the Lake Survey by Lieut. Col. Charles S. Riché, and reports from Francis Millet, chairman of the Niagara Falls committee was made to congress in House Document No. 246 (62d Congress, 2d Session, 1911-1912). Folio. 22pp., 10 plates (of 15 black and white photographs and 2 folding black and white panoramic landscape photographs.

The the last entry in the final report issued to congress in 1911, following 5 years of work on the condition of the falls and ways to save it for the nation, by Millet as Chairman of the Commission, shows Millet’s forward looking vision as an administrator and his efforts to develop the American culture.

“15, At the Whirlpool Rapids recently the scenery has been needlessly damaged and much vegetation destroyed erecting on private land an ugly staircase, a fence, and other structures, as shown in photographs No. 5 and No. 6. Such damage will continue so long as private selfishness and cupidity remain unrestrained.”

Excerpt from the life of Francis Davis Millet, by Michael G. Sullivan

During Millet’s lifetime, critics would sometimes demean his paintings with dismissive comments that most often centered on the suggestion that Millet would have been a better artist if he had only focused on his art. Millet was a people person, first and foremost, concerned about the human condition. The challenge, opportunity, or person with whom he was dealing, at the moment, was the most important in his life. Short-sighted critics aside, Cortissoz notes,

“Considering the immense amount of work that he did as an executive it is not unnatural to wonder how he got over the ground. The explanation lies in his work as a painter. It is careful, deliberate work. The temperament reflected in it is that of a man who would not be hurried. Such a man…could not have discharged all the duties he assumed if he had not had a thoughtful, quiet way of managing each day’s responsibilities. If Millet undertook to deal with a subject he made himself its accomplished master.”

Millet was not unaware that his willingness to step up and fill important rolls, outside of just being a painter, did in fact impact his artwork. In a letter to the drama and music critic Howard Ticknor (1836-1905), Millet lamented that he felt caught between the demands of being a painter and fulfilling callings that would benefit others:

“I always have twenty things more to do than I have time for. Like an idiot I accept a heap of outside work that limits my painting time and worries my life out of me. The longer I live the more I find it difficult to get a living. How do people do it? – by people I mean men who do nothing but paint pictures.”

A telling example of Millet being called upon to save something, rather than just focus on painting, was his appointment as Chairman of the Niagara Falls Preservation Commission, which preserved the falls as we know them today. As a result of that accomplishment, America’s greatest landscape painters such as Moran, Bierstadt, and others, had the beautiful landscapes of Niagara Falls to paint. We can still see the falls in their glory and hear the power of the water, absent the pile of manufacturing plants and dams that once crowded the banks and sucked up the water. Millet understood the cultural necessity that preserving a place like Niagara could provide. Today millions of visitors enjoy the falls, and you can always find someone painting them. What drove Millet to accept assignments, like the preservation commission, was his vision for the future of America. If he had listened to the critics and only “focused” on being a painter, Millet could have just practiced his technique and produced a beautifully executed Niagara cityscape – with a small rivulet running through it.

.

One of 13 murals, Millet designed for the Cleveland Trust building, completed in 1908 was Father Hennepin overlooking Niagara Falls.

Other special appointments Millet took on by the request of Presidents and Ambassadors were, for example, as the Director of Decorations for the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where, working once again with his close friend Daniel Burnham, he oversaw the artistic design and decoration of numerous buildings and venues, such as the decoration of the New York State Building, the Arts Building and the main promenade of the “Great White City.” itself. Where the use of large scale electrical lighting was used for the first time in the lives of many of the visitors to this watershed exposition. He selected the dozens of artists who took on major sculptural and mural work. Millet supervised all of this including the decorative effect of the Great White City itself, completing it on time and within budget.

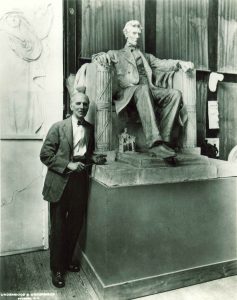

On other occasions in his life Millet was asked to represent America in Japan, Vienna etc at major exhibitions and on special assignments such as, working again with Burnham, they planned out the Washington Mall, with the Lincoln Memorial, as we know it today. Millet selected Henry Bacon as the Architect for the memorial, and fought hard to site the memorial itself in what was at the time a marsh by the Potomac; rather than the obscure location to the side of the DC railroad station that was being proposed by some powerful senators, who did not think such a major monument to Lincoln was warranted.

Having selected Daniel Chester French for the creation of a major statue at the1893 Columbian Exposition Millet tapped someone he knew well for the stature of Lincoln inside the memorial. Millet selected Daniel Chester French whose attention to detail, accuracy, and composition created the masterpiece we have today. Sadly, it was in another response to President Taft that brought Millet back from Italy where he was the Executive Secretary in charge of the American Academy of Art in Rome. Securing the fastest transportation back to Washington DC, in order to use his wit and persuasion with the leaders in Congress who were trying to derail the location and size of the Lincoln Memorial, Millet boarded the Titanic, thus giving up his seat on a lifeboat and among so many others giving up his life.