The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux

Date: circa 1905

Dimensions: Height: 193.04 cm ( 76.5 in.), Width: 312.42 cm (123 in.)

Medium: Painting – oil on canvas

Owner/Location: Commissioned by State of Minnesota for State Capitol building.

Description

Painted around 1905 by Francis Millet, “The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux”, depicting the treaty signing, does not attempt to be a historically accurate rendition of the look of the day, but attempts, as has been done for centuries with historical illustrations, to show all the various parties present during this historic event near present-day St. Peter, Minnesota, on July 23, 1851.

Millet attempted to show the dignity of the Dakota/Sioux Indians and possibly representatives of other interested tribes as a dignified people. Various other white traders, settlers and government representatives are shown. The primary document signed, between the United States and the Sissitunwan and Wahpetunwan bands of the Dakota Oyate (Nation), was one of 12 treaties signed with the Dakota between 1805 and 1858. Unfortunately other documents, that the Indians did not understand, relegated payments that should have gone to the tribes, was diverted to the settlers for “supposed” wrongs caused by the Indian nations.

As an example of Millet’s sincere efforts to portray the Native Americans accurately, the above preparatory sketch for the war bonnet wearing Indian in the back right of the painting was done from a real life sitting in which Millet used a Native American friend of his for many years to help guide his accuracy in painting the scene. The sketch is archived in the Academy of Arts and Letters, NYC, NY.

It is also interesting to note the white trader on the left of the painting who is holding under his arm a folded blanket, just like one being worn by the Indian in the front center of the painting. These blankets are referred to as Trade Blankets and were often moved across the nation by the white traders. This blanket and other items from tribes other than the Dakota’s have been used by some modern revisionist critics to claim Millet was insensitive or used other painters works to inspire his commissioned painting of the event. These critics ignore the wide trade practices of the Indian tribes for many goods ranging from blankets to flint products that moved from east to west and back during this period. For example, flint from Ohio has been found in Wyoming based Indian sites. It is important to recognize Millet, painting in the 19th Century, in his artwork did his best to fairly and accurately represent the cultures he was painting both in his genre works and his commissioned art.

For modern critics to try and project their mindsets into Millet’s mind and motivations is prejudicial and does not help improve our current historical scholarship.

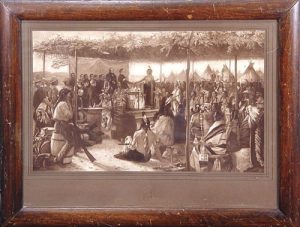

This painting at the time was quite popular as shown by the Carbon Print copy that is shown below:

149: S.W. Elson Carbon Print of Travers de Sioux

Allard Auctions, St. Ignatius, MT, US, Aug. 11, 2006, Est: $1,000 – $2,000

S.W. Elson Carbon Print Done by the famous Boston printmakers, this rare piece is of an original, very detailed work by F.D. Millet (1846 – 1912) depicting a treaty or ceremony; ex. Heye Foundation. 14″ x 22″ (22″ x 29″ framed)

https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/s-w-elson-carbon-print-149-c-yt98c72np6

Exhibitions / Provenance

Exhibitions:

Following the paintings commission by the State of Minnesota it was installed in the Capitol building in 1905.

Those wishing to see the painting themselves today, may find that it has been removed from view in the Capitol building and placed in storage. Please see Research tab.

Provenance:

Commissioned by the State of Minnesota in 1905 directly from the artist.

Literature

Research:

Historical background

Two 1851 treaties (the other being the Treaty of Mendota with the Bdewakanwunwan and Wahpekute Dakota) were intended to address two issues: land tensions between the Dakota and the region’s growing white population, and provisions of the treaty of 1837 not upheld by the United States. Negotiations for the Treaty of Traverse des Sioux lasted over three weeks. Between it and the Treaty of Mendota, the Dakota were to cede 35 million acres of land at 12 cents an acre in exchange for $3,750,000 to be paid over time—money that they never received. The Dakota were to retain a 20-mile strip of land along the Minnesota River, while the rest of their lands were opened up for Euro-American settlement.

Reluctant Dakota signers of this treaty included Istamahba (Sleepy Eye), Mahpiya Wicasta (Cloud Man), and Upi Iyahdeya (Extended Tail Feathers). American government representatives included Alexander Ramsey (governor of the Minnesota Territory) and Luke Lea (United States commissioner of Indian affairs). Also in attendance were trader Alexander Faribault and missionary Stephen Riggs, who served as interpreters.

After signing two copies of the treaty, the Dakota were led to sign a third document prepared by the traders, which had not been explained to them. Many thought it was simply another copy of the treaty. Instead, this document determined that monies promised to the Dakota for their land would instead go to traders for supposed “past debts.”

Today’s perspectives

Where Cass Gilbert and Francis Millet saw a coming together of cultures and the exchange of land and money that created the state of Minnesota, viewers of the painting today see a more complicated story. The treaty that was signed at Traverse des Sioux deprived the Dakota of their land and diverted the money they were promised to the fur traders. The depiction of the American Indians in the painting was also historically inaccurate. Millet based his painting on Mayer’s contemporary sketches, but the details in the painting were borrowed from other cultures and were not accurate representations of the Dakota present at the treaty signing.

[Millet documents in the Archives of the Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, do not support the conclusions of the Minnesota Historical Society that some details of the painting are inaccurate. Millet’s personal correspondence and sketches of then living Native American’s, some of which were lifelong friends, point to the extent to which Millet went to accurately portray the dignity of the Dakota/Sioux people as well as he could based on direction and materials held by then living Native American people to which he had access.]

MNHS staff interviewed a wide range of people with various perspectives on the painting. Interview subjects included Minnesota state legislators, historians, experts on western art, members of Minnesota’s Native American communities, and descendants of both the Dakota and the settlers involved in the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Their words illuminate the challenge of restoring the past in a building meant to represent all the people of Minnesota.

https://www.mnhs.org/capitol/learn/art/8961

[Those wishing to see the painting themselves may find it is some other location than the Reception Room for which is was created by commission or that it has been removed from view in the Capitol building and placed in storage.]

Publications: