Since the dawn of humanity, people have been using various forms of what can be called art to express their presence, emotion, hopes and dreams. Whether it is though hands painted in outline on cave walls or fetish statues made of clay, the general humanity in all of us can easily empathize with the need to express ones feelings and experiences. Through scholarship we can often decode much more than is readily apparent, for example we can date one set of hands in a cave from others 10,000 years later. We can also surmise the meaning of a large hand overlapping a small hand, in the same timeframe as more than a coincidence. We have cause to consider a more intimate bond between two people.

In the same manner that two overlapping hands painted in a cave can send meaning across time; the meaning that was current for the two people at the moment of creation may have been much different than our interpretation which is colored by our own experience and desires. So the scholar has an unenviable task to gathering as much data as possible and filtering it carefully against all other data in order to shake out the most reasonable understanding of what the actual meaning and use of an artistic creation was at its origin.

When over time changing values cause human beings to change the purpose or meaning of an artistic creation we have to be very careful to honestly identify our reasons for the alteration of purpose. Cultures that appropriate art for nationalistic purposes is only one example where the use and value of art can be corrupted. Equally difficult is the myopic “authority or critic” who pontificates upon the “mind of the artist or the motivation for creation” based upon the authority’s years of study or the consensus of a like-minded group of authorities ignoring their own bias.

Currently the “re-thinking” of white ancient statues of Greek or Roman origin is an example. For those researchers who cared to “see” decades ago we had ample examples of brightly painted statuary. It just wasn’t convenient to postulate anything other than white statues. In the same vein, critics today, who criticize the critics of yesterday fall into the same trap of their current social climate of “coloring” their judgement about the objectives and reasons for why painted sculpture was not commonly held to be the norm in Greek and Roman statuary. Just finding most of it without paint may have simply been enough, and no cultural appropriation was nefariously intended as a way one culture could dominate another. Xenophobia often thrown about today, really says more about the current critic claiming such a cultural climate than it does about a culture 100 or 2000 years before. Artistic purpose in painting or not painting a sculpture could be just as simple as bright colors show up better in non-illuminated spaces and believing sculptures were always created white could be as understandable as accepting them as they were commonly found and not thinking to look for the faint, lost, remains of color.

In todays culturally revisionist society, postulating that art of the past was primarily focused on creating an imagined idealistic society of yesteryear, is disingenuous at best; any more than saying current art is free from such a use. For example, when one looks at the mural of George Washington giving up his commission, literally no one would conjecture that such an idealized “royal” setting was remotely “the way it was.” Certainly no one living at the time of the murals creation would suppose such a fantasy was at all believable. Then what was the painter trying to communicate? By accepting the title of the work and what we see in the idealized setting is easy to understand that what is being valued so highly was the “act of giving up power,” as a virtue. While it is difficult to paint virtue, symbolic representation of an act can directly communicate such a value, while using the allegorical references and painterly style to communicate effectively. Other actions of Washington are relevant to this point about art. Washington was offered the Kingship of the country by congress following the Revolutionary War. He turned it down and clearly established an institution we know today as the Presidency, but Washington went further when he again “resigned” following his two terms in office, strengthening the fact that no person should hold continuous power just because they hold it at the time. Thus, we have numerous examples of art that portray these very acts by Washington, which in their very existence continue to visually remind us of our historical political foundation. But when a viewer looks at the numerous examples of Washington artwork they know they are not looking at photos of events but that the art is conveying a value that was central to the time in which it was created and today we can be thankful that was so since it reinforced the value of power to be found in the people and not one person.

Today to have modern critics, with their own agendas, reinterpreting the purpose of art from the past, simply because the creators and the viewers from that past are all dead is quite easy. This is not to say that art can never be used for propaganda purposes, of course that is not so. But to take whole artistic traditions such as romanticism or classicism and paint it with the broad brush of propaganda is irresponsible. While the great tradition of western portraiture may have a foundation in kings and queens sending portraits across vast distances, prior to photos, in order to help decide if they can stand the personal consequences of political decisions to marry is actually a bit humorous to consider. Henry VIII was a bit put out when he found he had been deceived by the court painter with his first marriage and thereafter sent his own artist to capture the correct likeness of his intended brides. Going forward it would be too much to ignore the value of portraiture in aiding self-esteem, fond memories, and many other reasons that portraits can smooth family relationships. Consequently, today the tradition of a portrait still lives, despite photography, because it can carry meaning and value by creating an understood fantasy that is not trying to change reality but convey emotion.

Since this website is dedicated to one man, Francis Davis Millet, and his artistic output, in painting, writing and administration, it is critical to understand that he was working in a different time and place, but that he had a visionary eye toward the future. While not all his work is a masterpiece, no artist has such a productive capacity, and not all Millet’s art was created to teach, prod, entertain, make people uncomfortable, or simply be fun or beautiful; the overall production of his work was quite different than that of the tradition of the day in which he lived.

At the Washington, DC memorial meeting following his death in 1912, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge described Millet in these terms:

“Behind the fun and laughter, the humor and the wit, back of the intelligence and the knowledge, one was always clearly conscious of the strong, brave man, the man of force and character. These, in happy combination, were the qualities which not only grappled his friends to him, but which enabled him to do such valuable and effective work in laboring for a public cause. He could convince, persuade and lead. He could make other men do what he desired without any sense of compulsion. Thus did he serve high purposes and achieve results of use and value to the world.”

It may have seemed minor when President Taft called upon Millet to chair the Preservation of Niagara Falls Commission, but it just the respect and relationships that Millet could build with all levels of people that was needed to tackle the ticklish challenge of saving Niagara Falls for posterity and balance that goal with all of the commercial interests that were vested in the water and power the river and falls provided. If it were not for Millet’s artistic vision and his unrelenting energy we would not have the Falls we know today. Millet understood what the Falls represented to the cultural foundation of America, why it needed to be preserved and how to get all of the competing interests to agree with that vision, otherwise we would have had another dirty little river and a dribble of water going over the edge of an over used natural wonder.

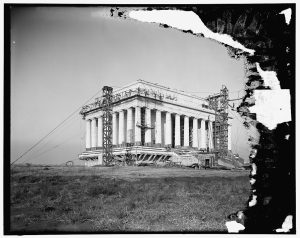

To this point of vison, another aspect of Millet’s life that has been forgotten or ignored, by critics of his life and his motives behind his artwork, was his presidential appointment as Vice Chair of the US Arts Commission. With Chairman, Daniel Burnham, Millet’s friend and collaborator on the 1893 Columbian Exposition, that together they laid out the plan for the Washington Mall and selected Henry Bacon as architect of the Lincoln Memorial. It was after a long and bruising battle over the creation of the Washington Mall and the placement of the Lincoln Memorial as the western anchor of the mall, that Congress reluctantly approved the plan. Congressional leadership initially wanted to place a small memorial next to the Union Train Station, by the Capitol. After Burnham and Millet selected Bacon as the Architect, Millet then led the commissioning of Daniel Chester French, to sculpt the statue of Lincoln for the Memorial. It was French, as Millet’s friend, that Millet had earlier tapped to be the creator of the massive “Republic” stature, which Millet designed, as the anchor for the northern end of the Columbian Exposition lagoon. Millet’s vison of the Lincoln Memorial was such that he knew French would create the iconic monument to Lincoln we enjoy today. Sadly, it was primarily, at President Taft’s urging that Millet returned to Washington from Rome, on the Titanic, in order to use his good influence with the leaders in Congress to finalize the vote for the Mall and Lincoln Memorial plan.

Millet may have lived in a romantic age, and he did paint topics that were often popular. But, when he painted a “Love Letter” for example, it was not like the hundreds of other such paintings done with adoring companions in the scene. It was of a young woman, set in a time and place that his audience could relate to, and the young woman was –alone– in fact she was more than alone, the only other person in the painting is who we assume is her father and he is totally ignoring her and her condition. To make matters worse, Millet painted on the floor between the two people a pile of discarded letters. This is not the traditional love letter scene, but it is reflective of Millets “parable” style of painting. Drawing upon his literary skills Millet built many of his canvases so they can be “read” at a number of different levels, based on the desire and experience of the viewer. Millet’s wit, and slightly sarcastic take on the common traditions of the time pushed him to paint a subtly different take on the expected composition in many of his paintings, Love Letter solidly being such a commentary, with a woman alone in her love moment.

A person cannot live the life of a young man, as a war correspondent and volunteer surgeon, cutting off limbs, sewing up the results of violent wounds and not learn to deal with reality. All of Millet’s multilayer paintings were not has light hearted as Love Letter. In Turkish Soldier we see a very tall canvas, of nearly 5 feet, portraying a colorful and exquisitely dressed Turkish Soldier. What is often missed is at his feet, in very dark shadow at the bottom left corner. The severed head of an opponent from the battlefield and the man’s body, with only feet showing can when studied be seen at the mid right side of the painting. The Bashi-Bazouk soldiers were known as fierce warriors who were very brutal with captives.

Millet was in the middle of the Russian-Turkish war as a correspondent and often was called upon to use his medical skills acquired from his father during the Civil War, to attend to both Russian and Turkish casualties. What most people do see in one surface layer of the Turkish Soldier painting, is the brighter head and face of a Caucasian man, with a deep concern or fear on his face leaning in from the left middle of the painting. He is a man who expresses subservience. Again what may not be seen is that the man’s hands are bound. Is he soon to be another victim? A casual observer will understand the overall “presence” of the soldier, but what likely will be missed, at a deeper level, is that the Turks lost the Russian-Turkish war and the face on the severed head may be that of the soldier, his own face, and the face of the man who seems to be a captive now may in fact be a part of the eventual Russian victors.

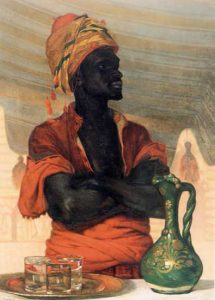

A third example of how much of a different approach Millet would take on a subject is found in his 1874 painting of the “Turkish Water Seller.” At a time in our history when the common public representation of blacks in America was commonly very derogatory, such as being portrayed as monkeys or other degenerate forms. In the “Turkish Water Seller” Millet presents a confident, handsome and very black man. Millet is saying with his art – look – I am a man to be reckoned with, I am someone of dignity and power, even though I am only a water seller. Millet in his multilayered approach to commentary would place a prejudiced person in a very uncomfortable position one that would cause the viewer to consider another point of view.

Royal Cortissoz in his 1923 book American Artists, noted key difference in Millet:

“Never was an artist more human, more sympathetic and more reasonable. Nothing in the world could ever have persuaded him to sacrifice a principle to expediency, but neither did he believe that his art required him to raise a barrier of esoteric mystery between himself and his fellow men.”

Art Critics would occasionally see this approach with Millet’s art and comment which would cause a creative stir around his paintings and be the catalyst for reflective conversation. One such high society painting was 5’x 6’ in size and a powerful portrait of the well-known feminist writer Kate Field. Field was a close friend of both Lily and Frank, so close in fact, that they named their daughter after her, Kate Millet. If nothing else, Millet was not a traditional follower of the times, though he lived fully in it. He truly loved all people and critics have taken swipes at him for that universal respect and appreciation for all men and women, no matter what race, culture, religion etc.

Indeed he painted beautiful women but he did not diminish them, he painted Colonial and Greek genre paintings but the detail was always accurate, the elements weren’t there just for “flavor.” Millet was so careful, unlike some of the better known painters of the day, he for example, had spent a massive amount of time studying Greek dress. So much time that he was considered the world’s expert and was asked to lecture on both continents. He sewed his own costumes and cobbled the sandals himself to be sure that they were correct. Essence was not enough, accuracy was always critical, and while art critics of the day, would often, understand the careful accurate detail, they rarely seemed to dive deep enough past the easy layers of Millet’s paintings to ask themselves – Why – did Millet paint that way and what was the message to be understood.

Again Cortissoz saw this:

“Considering the immense amount of work that he did as an executive it is not unnatural to wonder how he got over the ground. The explanation lies in his work as a painter. It is careful, deliberate work. The temperament reflected in it is that of a man who would not be hurried. Such a man…could not have discharged all the duties he assumed if he had not had a thoughtful, quiet way of managing each day’s responsibilities. If Millet undertook to deal with a subject he made himself its accomplished master.”

Millet never took on a project lightly. Even seemingly trivial or light hearted subjects were subjected to his close scrutiny of purpose. While 19th Century critics of Millet often missed the subtle layers of meaning in his artwork, 21st Century critics don’t even see any difference between Millet’s painting of a romantic subject, or even a troubling subject, and that of other contemporary artists such as Abbey, Tadema, or Sargent. While all were close friends and they often painted similar subjects, the viewer who is willing to take the time to understand Millet and his subject will find his work considerably more serious and compelling.

Consequently, as is so often the case with 21st Century criticism of Millet’s 19th Century creative and cultural contributions, various authors provide hundreds of pages and thousands of words that describe how “different” Millet was in his work and the “messages” he was presenting to his 19th Century audiences that were designed to challenge their assumptions and encourage reflection upon the valuable cultural differences he saw in the world. Millet did not, like 21st Century critics of our cultural actions, metaphorically “hit people over the head with a two by four.” Rather he would show the dignity and difference that made other cultures as valuable as the Anglo Saxon world in which he was born.

Sadly, 21st Century critics often present the factual differences in Millet’s work, and then blindly place their own 21st Century self-loathing or “embarrassment” of 19th Century values above them. The facts that surround Millet’s artwork and writing, often called into question the 19th Century values. When considering the factual presentation of Millet’s artwork and writing, the conclusions drawn by the 21st Century critics are often, not congruent with the very facts they have presented about Millet’s work.

21st Century critics present the facts about Millet’s work, and then blindly ignore those very facts in their conclusions about Millet’s objectives. The reader of the facts presented in any review of Millet’s work are encouraged to come to their own conclusions about Millet’s message and what it represents. The conclusions drawn may not be the same as the authors who have provided the factual review.